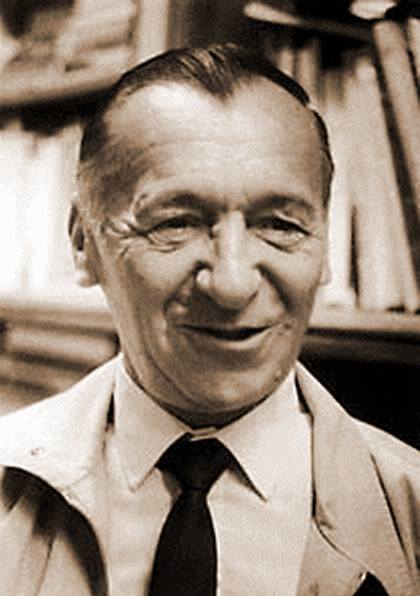

Narodený: * 1913-05-30, Podbiel

† 2000-10-23, Praha, Česko

Spisovateľ, diplomat, literárny vedec, pedagóg.

V mladosti bol na Slovensku aktívny v Ha-šomer ha-cair (ľavicová židovská mládežnícka organizácia), neskoršie sa stal komunistom. Študoval na Filozofickej fakulte Karlovej univerzity v Prahe. Publikovať začal počas štúdií v časopisoch Podrast, Vesna, Slov. východ, Slov. pohľady.

Do roku 1939 pôsobil v Prahe ako tajomník Ligy pre ľudské práva a učiteľ. Cez vojnu v exile a na čsl. veľvyslanectve v Londýne. 1947-1949 bol zástupcom čs. veľvyslanca v Londýne, do roku 1951 vyslanec v Tel Avive v Izraeli. V roku 1951 ho v ČSR vo vykonštruovanom súdnom procese odsúdili na doživotie. V roku 1955 ho rehabilitovali, prednášal na Katedre germanistiky Filozofickej fakulty KU v Prahe.

Po okupácii Česko-Slovenska v roku 1968 emigroval, bol hosťujúcim profesorom porovnávacej literatúry na univerzitách v Sussexe v Anglicku, v Štokholme, Los Angeles a v Kostnici. Od roku 1991 žil v Prahe.

Je autorom kníh Rainer Maria Rilke und Franz Werfel (1960), Na tému Franz Kafka (1964), Da Praga a Danzica (1981) a i.

Foto: www.kafka.org

Odkazy

Eduard Goldstucker

Writer, diplomat, 1913-2000

He was one of the last surviving protagonists of the Prague Spring of 1968, and during that time was the chairman of the Czech Writers' Union and deputy vice-chancellor of the philosophy faculty at Charles University. Professor Eduard Goldstucker has died aged 87.

Goldstucker had many close friends and colleagues in Britain. The turbulent events in his homeland caused him to seek refuge in Britain twice: first, in 1939 as a young Jewish communist fleeing the Nazi occupation, and second, after the Soviet-led invasion of 1968. He was also professor of comparative literature at Sussex University.

Goldstucker was born in a small town in Slovakia, studied in Prague and later, during his first exile in Britain, at Oxford. He joined the Czechoslovak Communist Party in the 1930s during the rise of fascism in Germany, and was then most active in anti-fascist organisations.

In Britain, on completing his studies, he joined the Czech government in exile. Near the end of World War II, he was appointed to the Czech diplomatic service, and had postings in Paris and London. He became the first Czech ambassador to Israel in 1950.

The Stalinist regime had been established in Czechoslovakia in 1948 and by the early '50s purges were in full progress. Goldstucker was recalled from Israel and arrested. He was one of those involved in the show trials. Having spent the war in the West and being of Jewish origin, he was a natural target. The prosecutor demanded the death sentence, which was later commuted to life imprisonment. Goldstucker spent his years in jail under the most inhuman conditions.

During the political thaw following Stalin's death in 1953, Goldstucker was released and began teaching German studies at Charles University. He was known for his work on Franz Kafka and Prague's German-speaking writers. In 1967 he organised a conference on Kafka, an event remembered because the regime had always suppressed Kafka's works, labelling them „hostile to socialism“.

As chairman of the Czech Writers' Union, and as a member of the Czech parliament, he played a leading role in the movement to reform the repressive regime and restore freedom of speech – the 1968 Prague Spring. He was working for the restoration of the ideals of socialism that had brought him into the left-wing movement and to which he remained faithful.

The Soviet-led invasion in August 1968 forced him to emigrate. Accompanied by his wife Marta he returned to Britain and the Sussex University professorship. He also lectured at various Western European literary institutions. His memoirs, written during this period, have so far been published only in German.

After the collapse of communism in Czechoslovakia, Eduard and Marta returned to their native country, where their daughters, Anna and Helena lived. He was anxious to offer his knowledge to a country being reborn, but the new establishment was not interested. As a „68er“ – an erstwhile reform communist – he spent his last years almost as a non-person.

Yet Goldstucker was greatly respected, loved and honoured by some of Germany and Austria's most prestigious academic institutions.

He is survived by two daughters, five grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.